Simple products are easy to use. That much is self-evident.

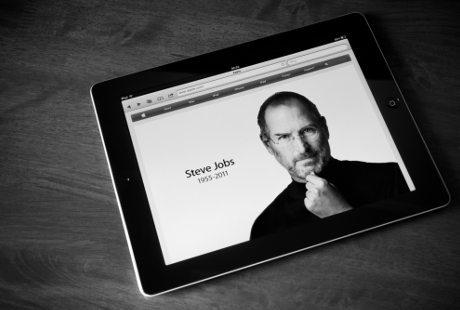

But according to Ken Segall, an advertising executive who worked with Apple founder Steve Jobs for 12 years, the "power of simple" stretches beyond just usability.

"Being simple makes you better liked," he said at the Digital 2013 conference in Wales earlier this week.

The proof, he says, is Apple's remarkable popularity. The company sells products with simple user interfaces – look at the iPhone with its single button, he says – and customers repay the company in seemingly undying loyalty.

"In Steve Jobs' world, if you had a better idea, you could do it."

"Steve said time and time again that our goal was to make people love Apple," he says. "And I think he really believed that if you could make something functionally simple and beautifully designed, people would have to have your products."

The principle of simplicity permeates Apple, from its products themselves to the limited range on offer. Apple has just six laptops on sale, Segall observes. Contrast that with rival PC makers Dell and Hewlett-Packard.

"Dell has 42 distinct models on its website and HP has 49," he says. "But Apple makes more money with its six models than Dell and HP combined."

Funnily enough, Dell is well aware of the issue. In his book Insanely Simple, Segall wrote that the PC maker could one day announce to the world that it was focusing on just four amazing models. "The world would go 'wow'."

After the book was published, Segall was contacted by Michael Dell himself. He has visited the company twice to present his ideas, Segall says, "and they all agree."

"They all say, 'We've had this problem for years. We should definitely cut down our models."

Simple processes

So why can't most businesses achieve the simplicity of Apple, even when they want to? It has a lot to do with the way companies operate, says Segall, especially their approval processes.

Segall contrasts the way in which Apple took decisions with another former client, chipmaker Intel. "At Intel, I felt that processes had taken priority over ideas," he says. "If the process was already underway, and you came up with a better idea, it would be ignored because people were already expecting the first idea."

"In Steve Jobs' world, if you had a better idea, you could do it."

That was in part due to Jobs' own involvement in the ideation process. He would be present at the early meetings about a project, Segall says, so he would be able to judge the relative benefits of new ideas.

But it must also have had something to do with Jobs' stature within the company after his return as CEO in 1996. If an idea had his support, it would have the support of the whole organisation, and not every company has this kind of leadership.

That said, not everything Jobs touched turned to gold. Segall also worked with NeXT, the workstation maker Jobs founded after being ejected by Apple's board in 1985. NeXT's technology has its fans, but it is not considered a commercial success.

So if Jobs' focus on simplicity is so effective, why did NeXT fail to take off?

For one thing, Segall says, Jobs' reputation had been damaged by his split from Apple. "He had been humiliated," he recalls. "His business savvy had been called into question."

But also, NeXT was a much harder sell. "Steve was offering a simplified solution to enterprise computing bit it was a tough sell because it required ripping out millions of dollars-

worth of stuff they already had."

Jobs’ experience at NeXT will be familiar to any IT leader who has tried to instill a degree of simplicity in their organisation’s IT environment, only to find a complex mesh of entrenched systems.

Still, with users growing ever more powerful in IT buying decisions, it would be wise to consider the lessons of technology’s most popular mogul – and the impact that internal processes can have on the simplicity of products.