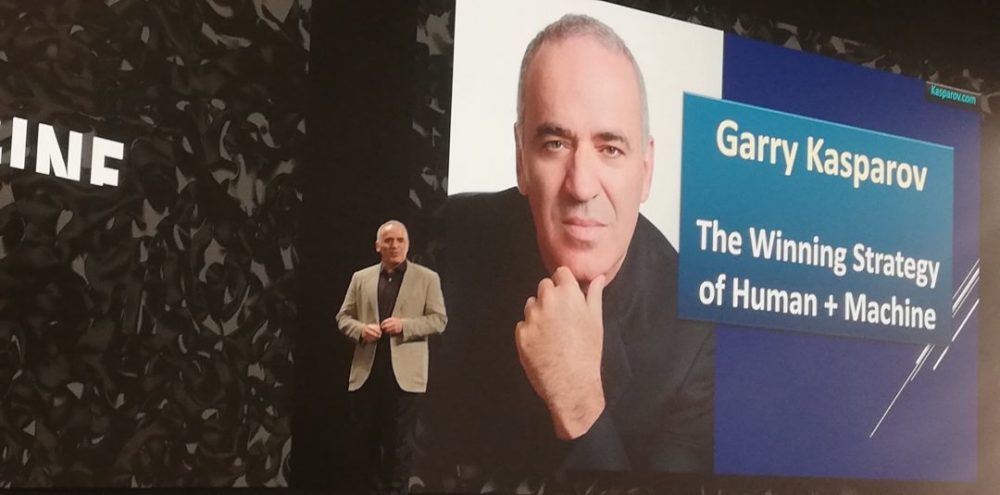

Kasparov and AI

“Chess used to be connected to the mysteries of human intelligence,” said Garry Kasparov speaking at the recent Automation Anywhere conference in London. Kasparov, who has been described as the greatest chess player ever, struck a humble note when he qualified that statement, by suggesting that “it isn’t true.” Alfred Binet, the father of IQ tests, was one of the first to suggest a link. “It’s flattering,” said the chess genius, “as a professional player I can tell you that the aptitude for playing chess, is not much more than the aptitude for playing chess.”

To let you into a secret, the author of this article suspects that Kasparov is a pretty clever bloke, but he made the point well.

When in 1996 IBM’s DeepBlue won a game off Kasparov, from a set of six, his first defeat in 12 years, it did not mean computers had suddenly become intelligent. Today, as Kasparov pointed out, a chess app running on a typical smartphone would have given the DeepBlue of 1996, or of 1997, when the computer actually defeated Kasparov over the entire series, a good thrashing.

But few people would say a smartphone is intelligent. Just as being good at chess does not define intelligence, it would appear being smart doesn’t either, especially in the context of phones.

Maybe, we can’t really get past 2001 — that’s to say Stanley Kubrick’s Space Odyssey which we can’t get past, H(I)A(B)L(M), a sentient machine and music from Richard and Johan Strauss, representing the AI threat to humanity.

It was not just Binet, the likes of Alan Turing and Norbert Weiner also thought that the day a computer could defeat us humans at chess was the day we had machines with intelligence.

These geniuses, from yesteryear, erred, suggests Kasparov, and understanding why is the point.

To err is to be human — computers can beat us at chess, not because they are intelligent, but because they don’t make mistakes.

The computer that defeated Kasparov could compute 200,000 moves a second, “But it was as intelligent as your alarm clock.”

Today, suggested Kasparov, the gap between a chess program you can download onto a laptop computer, and Magnus Carlsen, the best human chess player in the world, is about the same as the gap between a Ferrari and Usain Bolt.

It does seem, though, that the relationship between machine and people is typified by one between Kasparov experienced at the hand of computers. At first, Kasparov was far superior. Then there was a short window when computers and humans were closely matched, and then the computer moved far ahead.

It was after the defeat, that Kasparov had his big idea: human creativity in tandem with a computer’s brute force and memory, what Kasparov calls ‘advanced chess.’

Human + computer = advanced chess

The trouble with computers is that they only provide answers; it is up to humans to set the questions.

And that takes us to the nub of Kasparov’s argument. We must stop using phrases such as artificial intelligence, “instead say augmented intelligence,” he says.

If we see computers as ways to augment us, allowing humans to focus on what we are good at, computers on the number crunching, memory intensive work, we can work in harmony with the machine.

Gartner: debunking five artificial intelligence misconceptions

“AI is not a magic wand; it is not Terminator; it does not mean dystopia; it is just a tool. Treat it as a tool designed to make lives simpler.”

Claude Shannon, the American mathematician, known as the father of information theory, described three types of machines playing chess.

- Type A: machines are computers applying brute force;

- Type B: a selective search looking at “important” branches only — what Kasparov calls advanced chess;

- Type C: is the future, operators guiding groups of algorithms, where computers can generate their own knowledge based on human-produced frameworks.

But we are nowhere near there, the public perception, influenced by the Hollywood thirst for drama, is not in touch with reality. “The public thinks we are at Windows 10 when we are at MS-DOS,” said Kasparov.

Automation disrupts employment but creates new jobs

History tells us that automation destroys jobs and creates new ones.

But “protecting jobs that can be replaced by machines is just prolonging the agony,” said Kasparov.

But what we need are trained operators, Kasparov described our future role as being like shepherds for machines.

Thank God it’s Monday: Can automation really make us love our jobs again?

There was a time when Hollywood had a positive interpretation of computers — in Star Trek, humans and computers working together. Then Terminator showed a much darker vision. Except, from the second Terminator film onwards, machine and human working together, defeated the much superior machine.

With pride, Kasparov revealed an image of him playing chess with the Terminator himself, Arnold Schwarzenegger. “I decided it was best to let him draw” laughed Kasparov, but man and machine together might just be the future of AI, either that or its checkmate for humanity.