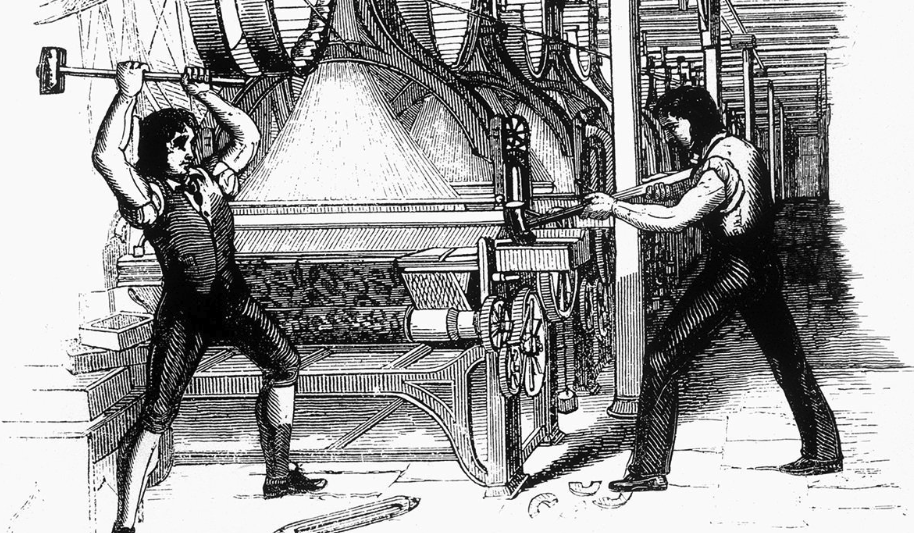

“No one looks back now and thinks: I wish the Luddites had won, said the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Amber Rudd, recently. She was bringing up that old chestnut of whether technology destroys jobs.

“In the Nineteenth Century, blacksmiths were replaced by railwaymen. It was not an easy transition, but ultimately the productive value of labour increased, and an explosion of commerce and communication followed,” she said, and she is right, of course. But can today’s displaced workers retrain as data scientists, complete with PhDs?

“As we progress towards the 100 year life, as the economy transforms around us, we know that multiple career changes are likely to become the norm. Changing career, perhaps several times, in the midst of working life can be daunting – particularly if you have a family to look after. I know – that’s the path that I took,” said Rudd.

Those who work in the automation business, such as RPA companies, for example, often go further. They say automation can make working more fun.

“We think we have automated 10-20% of processes using traditional technologies,” says Neeti Mehta, SVP, Brand and Culture Architect, at RPA company Automation Anywhere, “with that we have increased life spans by 25 to 30 years, we have been to the moon. With RPA and AI, we think we can automate another 40% to 50%, think what you can do for humankind if we can free them up from that repetition.”

Guy Kirkwood, chief Evangelist at UiPath cites a customer of UiPath, who said. “The mood music has changed, our people are happier, and we now measure the service in terms of compliments rather than complaints.”

Apparently, then technology does not merely make work more fun, it goes further than that, it creates happier workers.

Thank God it’s Monday: Can automation really make us love our jobs again?

As Ms Rudd said: “Automation is driving the decline of banal and repetitive tasks. So the jobs of the future are increasingly likely to be those that need human sensibilities, with personal relationships, qualitative judgement and creativity coming to the fore.” Let’s face it, personal relationships, qualitative judgement and creativity are more fun than most tasks we do at work.

Maybe we will see a great gale of Schumpeterian creative destruction, destroying jobs for sure, but creating more fun jobs in the process.

According to research; carried out by Dr Chris Brauer, and his team, at the Institute of Management Studies, at Goldsmiths University, University of London, and produced on behalf of Automation Anywhere, 58% of work activities, and 30% of tasks can be automated by robots, but only 5% of jobs.

The Automation Anywhere commissioned study shows that organisations augmented by automation technologies are 33% more likely to be ‘human friendly’ workplaces, and 78% of employees said that RPA allows them to focus on the more creative and strategic parts of their jobs. In fact, the study shows that it’s only by investing in people alongside automation, that businesses will get the most out of the technology.

Automation Anywhere said: “Further academic research we supported, shows that the majority (72%) of workers surveyed don’t fear automation or AI and two thirds (66%) actually want to know more about how the technology can help them do their job. When implemented correctly, these technologies not only improve efficiency in business functions, but can also lead to more engaged and happier employees.

Earlier this year, the ONS released a report saying 1.5 million jobs are in danger of being in some way automated.

Staying ahead of the curve as automation takes jobs

Maybe we should refer to one-time chess grandmaster, Garry Kasparov who said “technology is the reason why people are alive to complain about technology.”

Yet, complain we do. Roughly 200 years ago, the Luddites went around smashing up machines, so great was their fear; today we have academics and now esteemed compilers of statistics, such as the UK’s Office of National Statistics (ONS) warning about how jobs are under threat from automation. But are they right? Or is technology simply meaning we are living longer, so that we can spend even more time complaining about it?

“The first industrial revolution began around 1760, with the Spinning Jenny,” says Guy Kirkwood, “prior to that, 98% of the population worked the land, now it is just 2%, but that does not mean that there was 98% unemployment.”

AI won’t destroy jobs it will transform them

The chorus of voices claiming that AI won’t destroy jobs is getting louder

Kirkwood said: “Robots will become net job promoters, they will create more jobs than they eliminate.”

Part of the problem with studies proclaiming job losses is that they tend to focus on tasks and not the overall activities a worker might carry out. Take the classic study, from Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, from Oxford University’s Future of Employment report.

So sure, some tasks might become the preserve of automation, but that does not mean the jobs will.

In fairness to the ONS, it did say “Around 1.5 million jobs in England are at high risk of some of their duties and tasks being automated in the future.”

Does that mean we are worrying over nothing? That automation and job creation are like a horse and carriage, which supposedly go together like love and marriage?

The lesson of history

According to economist James Bessen, in the early days of the industrial revolution, while productivity rose, wages did not rise in tandem. At first, each factory owner was quite proprietary about the technology they used. They would train workers to use it, but the skills the workers gained were not transferable, as a result, the employer had a kind of monopoly in the local labour market. It was not until, many decades later, that technology, supported by trade associations, became more homogeneous, and a labourer at one factory who had acquired certain skills found they could work for someone else and apply the same skills. At that point, wages rose. But the impact on the factory owner was still positive; rising wages created a more buoyant economy. There might have been ‘trouble at mill’, but not because of a lack of demand for products.

Or take another example, according to British army records, average height, a proxy for health, declined in the mid-years of the 19th century, before rising.

Scaling RPA: before automating processes, improve them

In short, it took time before the benefits of automation filtered through to the labour market.

Indeed, on this theme, Carl Benedikt Frey has a new book to be published shortly, ‘The Technology Trap, Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation‘ comparing the experience of the Industrial Revolution to our age of artificial intelligence. In the book, he argues that much of the social and political polarisation that we are seeing is due to rapid technological change.

As Neeti Mehta said: “As companies transition their workforce, and make it bot enabled, we must look at this ahead of time. When we look at history and look at every industrial revolution, we always dealt with it but in the aftermath, now we have that history behind us, why not deal with it as we are transitioning?”

In other words, learn the lesson of history, and apply it in advance of any social upheaval that may result from automation.

On this theme, Frey said: “It is true that automation has reduced the need for routinised chores and has primarily taken over repetitive and boring jobs. However, many of these jobs, especially those in manufacturing, were the ones that supported a broad and relatively prosperous middle class. As manufacturing jobs have dried up, industrial cities, and the people living there, have experienced a reversal of fortunes.” Maybe we have already been failing to learn the lesson of history — if Frey is right, technology has played a role in creating the recent social upheaval which we read about almost every day.

Tasks not jobs

That view may well be right in a more general example of automation replacing jobs traditional jobs in manufacturing, but in the area of RPA, or robotic process automation, things may be different.

As Guy Kirkwood said, technologies like RPA are not about “replacing jobs, rather they free people up to do more fun activities.”

Thank God it’s Monday: Can automation really make us love our jobs again?

Or, as Neeti Mehta said: “People weren’t put on Earth to transfer data from one system to another, but that is what so many of us do. Nobody wants to fill in invoices manually, or reconcile invoices manually using eyesight, instead, we want to create better products, innovate or have a four-day work-week.”

The future of jobs

The ONS produces statistics; it does not speculate on what jobs that currently don’t yet exist, or are rare, will become popular.

It is certainly the case that some jobs will be destroyed by technology. Taxi drivers are not looking forward to the age of autonomous cars.

Other jobs will be created

Cognizant has produced a report, 21 More Jobs of the Future, Euan Davis, European Lead, at Cognizant’s Centre for the Future of Work said that the report “predicts that roles such as a cyber-attack agent or juvenile cybercrime rehabilitation counsellor will emerge in response to new types of warfare. Alternatively, positions such as voice UX designer will help individuals curate their perfect voice assistant, while machine personality designers will develop a unique character for digital products or services.”

Fear mongering

So is it fear mongering?

John Everhard, Director at Pegasystems, said that “headlines that lambast workplace automation are merely counterproductive. Rather than instilling fear in the youth of today via research that criticises AI, we need to promote the use of the technology in the workplace so that young people are more aware of its benefits and uses when they enter the workforce.”

Euan Davis said: “The rapid evolution of working practices has resulted in skills resembling mobile apps, requiring frequent upgrades to stay relevant. Ultimately, the AI revolution will create as many, if not more jobs than it takes away. However, as the world of work continues to evolve based on new technologies, humans must increasingly evolve their skill sets to stay relevant and work in harmony with technologies, to ensure their jobs are not automated away.

UiPath: RPA and the job destruction myth

Ethics by design

But the transition may not be simple. How many former taxi drivers train as data scientists?

These are problems that vex some. At a recent Automation Anywhere, event, Dr Chris Brauer, talked about ethics by design. How organisations must build ethical considerations into their practices as they implement innovation, not after.

Neeti Mehta said: “That there is a commercial benefit as well as a social benefit to care about ethics.

“If you are not able to take your best resource, which is humans, you have lost.

“History tells us you have to deal with these issues eventually; it is better to deal with it at the beginning.”

Guy Kirkwood focuses on how innovation can improve working lives. “In Japan the average Japanese employee works 60 hours a week.” And in the land of the rising sun, there is a word for ‘working to death; Karōshi. If Kirkwood is right, it is not jobs that will be destroyed by technology, it is Karōshi.